Shoulder Labral Tears

A board-certified, fellowship-trained orthopaedic shoulder surgeon and sports medicine specialist, Dr. Steven Chudik is renowned for his shoulder expertise and innovative procedures that reduce surgical trauma, speed recovery and yield excellent outcomes. Through his research, Dr. Chudik investigates and pioneers advanced and novel arthroscopic procedures, instruments and implants that have forever changed patients’ lives. Never content to settle for what’s always been done for orthopaedic shoulder, Dr. Chudik prides himself on providing individualized care and developing a plan that is right for each patient.

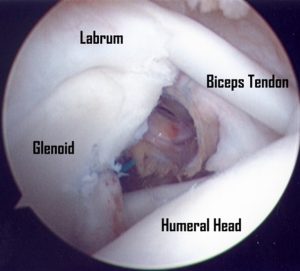

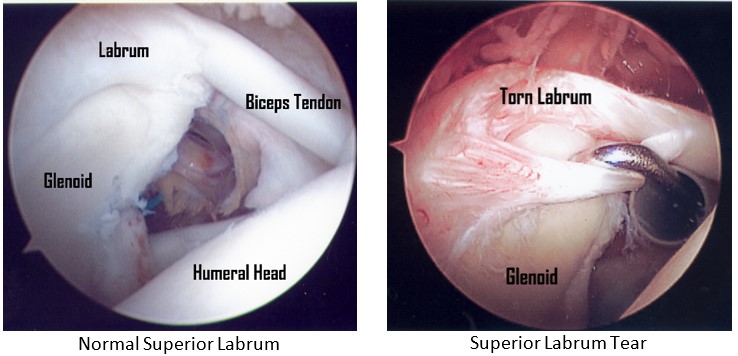

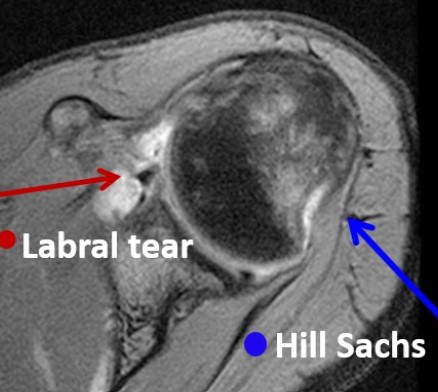

Labral tears generally occur from occur from overhead sports or an injury with the arm extended overhead. Labral tears do not heal themselves because of their limited blood supply and the movement and instability of the torn portion; therefore, they typically require surgery. This tear may take the form of degenerative fraying, a split in the labrum, or a complete separation of the labrum off the bony glenoid. SLAP tears will often involve damage to the biceps tendon attachment. Superior labral tears can be difficult to see on MRI and are discovered only during arthroscopic surgery.

Shoulder Labral Tear Expertise

- Superior Labral Tear

- Anterior Bankart Tear

- Posterior Bankart Tear

- Bankart Repairs and Reconstruction

- SLAP Tear

Individualized Treatment and Rehabilitation

Because no two people and no two injuries are alike, Dr. Chudik uses his expertise to develop and provide individualized care and recovery plans for his patients. This customized attention explains why patients travel to have Dr. Chudik care for their shoulder conditions and injuries.

To ensure his patients can return to sports and activities safely, Dr. Chudik researched and developed a return to sport functional test protocol that provides objective measures for both the athlete and Dr. Chudik to know when it is safe to return, as well as what else needs to be done if the athlete fails to pass the exam.

Frequently Asked Questions

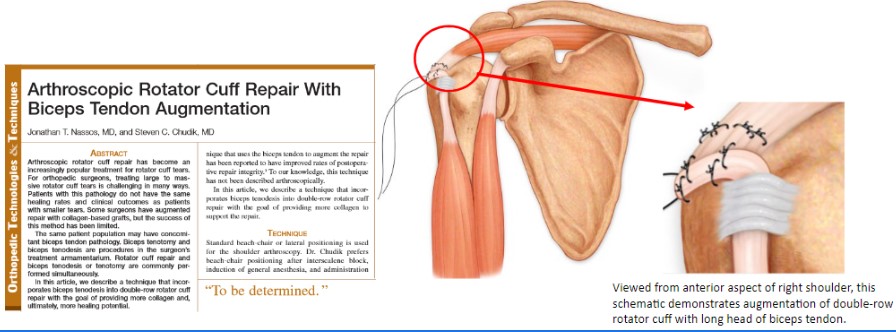

The labrum is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that circles the peripheral rim of the glenoid (socket of the shoulder). The labrum functions as the attachment site of the shoulder capsule and ligaments that run between the humeral head (ball) and glenoid (socket) of the shoulder to provide stability. The long head of the biceps tendon also attaches to the superior (upper) bony glenoid (socket) by its attachment through the superior (upper) labrum. Injury to the superior labrum is referred to as a SLAP lesion (tear), which stands for Superior Labrum, Anterior to Posterior (front to back). This tear may take the form of degenerative (wear and tear) fraying, a split in the labrum, or a complete separation of the labrum off the bony glenoid (socket), with or without damage to the biceps tendon attachment. Superior labral separations also result in some lesser amounts of shoulder instability. Superior labral tears are sometimes difficult to see on MRI and are sometimes only found during arthroscopic surgery (see arthroscopic pictures below).

- Physical therapy with focus on dynamic shoulder stabilization

- Limit activities that involve shoulder/body contact, overhead movement, throwing, and diving

Many labral tears are not symptomatic and do not need surgery, especially if they are degenerative or if the patient does not perform strenuous repetitive overhead activities. Labral tears do not heal by themselves because of their limited blood supply and the instability (continued motion) of the torn portion. Therefore, if they are symptomatic, they typically require surgery. Physical exam findings are not sufficiently specific to reliably make the diagnosis of a labral tear. MRI and MRI arthrograms (MRI following dye injection into the shoulder) are limited and can fail to show clinically significant labral tears. Thus, after an acute shoulder injury with a history and physical exam findings consistent with a SLAP tear, conservative treatment of physical therapy is often needed to determine if the injury will improve without surgery. After four to six weeks of proper shoulder therapy, the majority of milder sprains or strains (that do not need surgery) will improve and actual SLAP tears will continue to cause symptoms and produce pain with specific physical exam tests. Following surgical treatment, SLAP tears often heal and symptoms improve dramatically.

- A particular type of sling is typically recommended (and provided in clinic prior to surgery) for protection for approximately 6 weeks after surgery. Dr. Chudik recommends that you wear the sling at all times after surgery. You are encouraged to come out of the sling several times per day and move the elbow/hand/wrist to prevent them from becoming stiff. You may remove the sling to shower according to your post-op instruction sheet.

- The sling is a good reminder for you to be careful with the shoulder after surgery. It is also a signal to those around you to be careful, so it is especially important to wear your sling at work/school and in crowds.

- Surgery for the superior labrum often requires addressing the biceps tendon as well. If the biceps also has to be repaired, you will not be allowed to use the surgical arm for approximately 6 weeks after surgery.

- After surgery, physical therapy is critical to prevent and treat stiffness of the shoulder. Most cases of stiffness can be improved by therapy and home exercises.

- It is important that you also spend time every day (outside of formal therapy) during recovery doing the prescribed exercises to improve your range of motion. After the sling is removed, Dr. Chudik recommends frequent (hourly) stretching.

Testimonials and Patient Stories

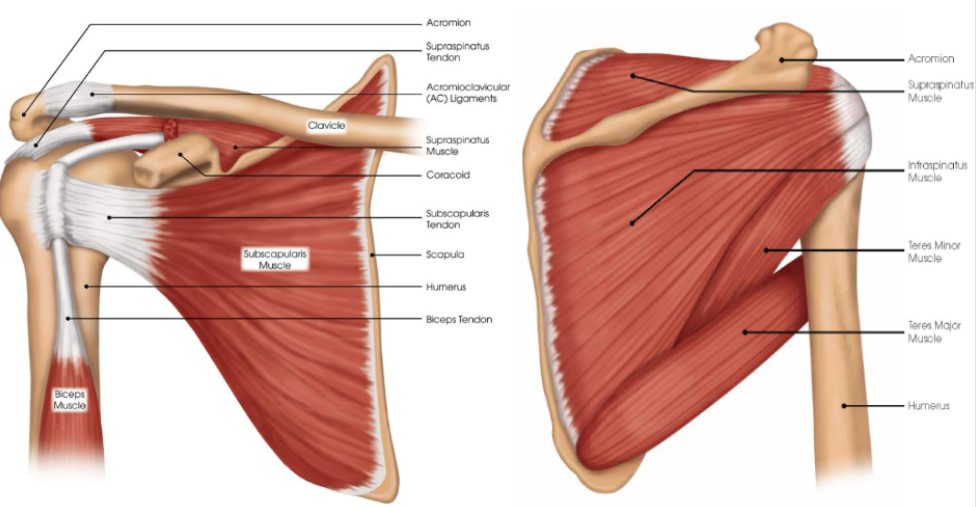

Shoulder Anatomy

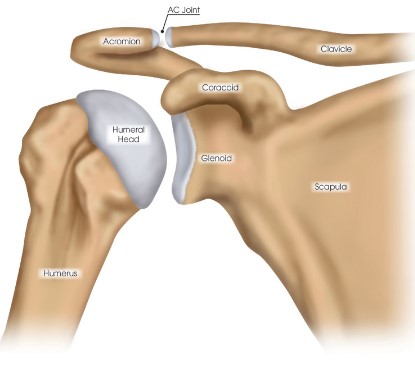

The shoulder has a remarkable range of motion, making it one of your body’s most mobile and important joints. Whether you are throwing a baseball, working overhead, or performing everyday tasks of reaching and carrying, your shoulder motion is critical to this high level of function. Unfortunately, this increased mobility and structural complexity makes your shoulders susceptible to injuries that can be quite limiting and disabling.

Shoulder

Scapula (shoulder blade)

Clavicle (collar bone)

Humerus (upper arm bone)

Glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint)

Acromioclavicular joint (shoulder blade-collar bone joint)

Sternoclavicular joint (sternum-collar bone joint)

Scapulothoracic articulation (shoulder blade-chest connection)

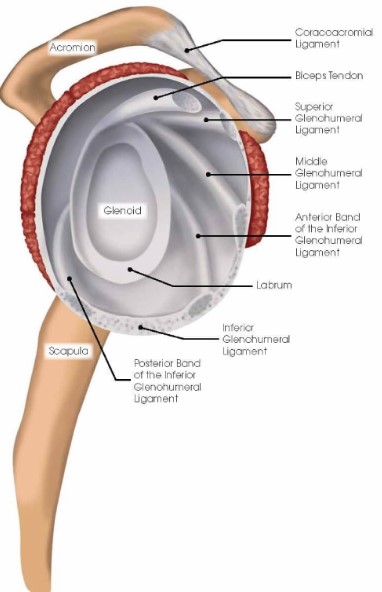

Labrum and Ligament Anatomys

The shoulder has a labrum or thickening of firm soft tissue attached to the rim of the glenoid (socket). It deepens the socket to increase stability, bears load and is the attachment point for ligaments that run between the upper arm bone and the bony glenoid (socket). Ligaments are strong soft-tissue bands that connect bones at a joint and provide stability and proper limits to motion. The labrum and ligaments may be torn if forces cause the humeral head (ball) to abruptly shift from the glenoid (socket) such as during a shoulder dislocation. Shoulder ligaments get their names from the bones to which they connect and include the superior glenohumeral ligament (SGHL), middle glenohumeral ligament (MGHL), and the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) with important anterior and posterior bands. Other important ligaments in the shoulder include the acromioclavicular, coracoclavicular, and sternoclavicular ligaments.

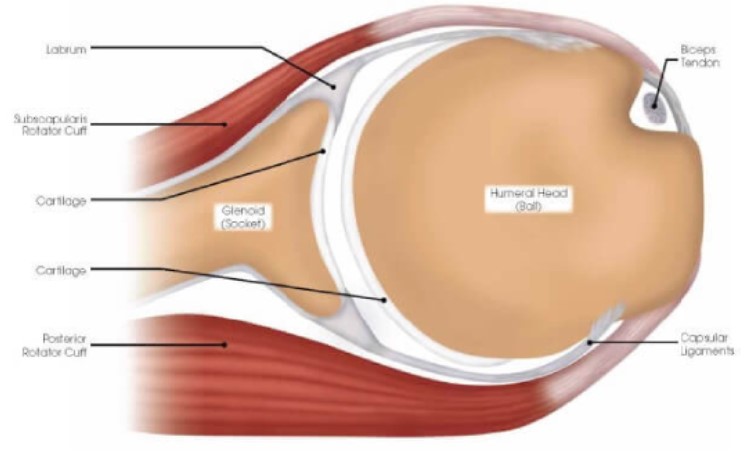

Cartilage

The joint surfaces of the shoulder are covered with a thin, but durable, layer of cartilage over the ends of the humeral head (ball) and glenoid (socket) that allows the shoulder surfaces to articulate, and move smoothly—almost frictionless and painlessly along each other. The cartilage lacks a blood supply. It gets nutrition from the joint fluid. Without a blood supply and because of its relatively less active cellular makeup, cartilage does not maintain or repair itself. The cartilage is extremely durable, but in time with “wear and tear” or following injury, it breaks down, fails, and leads to cartilage damage and eventually symptomatic (pain, stiffness, swelling) arthritis (failure of this protective joint surface).

Muscles

The shoulder has several muscles that help it move with proper coordination and strength to accomplish tasks ranging from simple reaching to high-level overhead athletic maneuvers. Muscles are like loaded active springs. They attach to bones across joints by different-shaped rope- or band-like tendons to exert their action and cause movement. The rotator cuff is a deep, core group of four muscles. They keep the humeral head (ball) centered on the glenoid (socket) while the pectoralis major, deltoid, and latissimus dorsi (the big muscle movers of the arm) create pulling and pushing forces that would otherwise shift the humeral head out of the glenoid (socket). Even with simply reaching out and away from your body the rotator cuff must generate forces equal to almost 80 percent of your body weight to keep the humeral head centered in the glenoid. Still, greater forces are needed during overhead throwing or strenuous lifting movements. These tremendous forces can cause tears in the tendon portion of the rotator cuff and result in pain and arm/shoulder limitations. The long head of the biceps muscle that attaches to the top of the glenoid through the superior (top) labrum can also be injured and cause pain. Additionally, muscles control the shoulder joint’s scapula (shoulder blade) or base, which can be affected by injury and overuse producing shoulder pain and limitations.

Injuries & Conditions

Surgical Procedures

- Superior Labral Repair

- Biceps Tenodesis

- Bony Bankart Repair

- Bankart (Labrum) Repair – Anterior

- Bankart (Labrum) Repair – Posterior

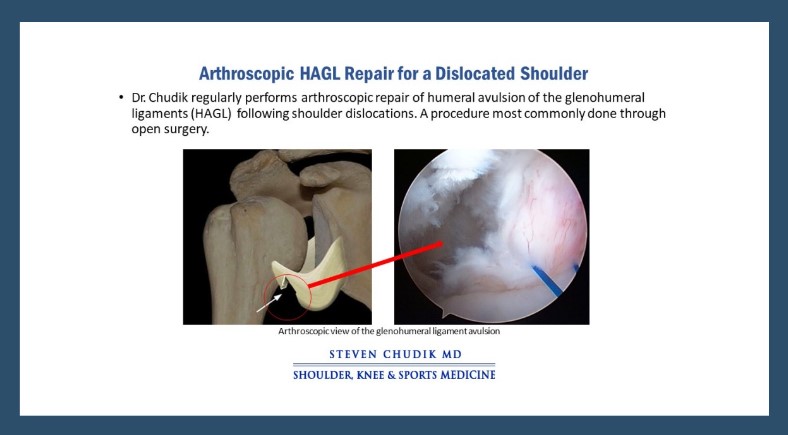

- Arthroscopic Repair of Humeral Avulsion of the Glenohumeral Ligaments (HAGL)

- Arthroscopic Bony Bankart Repair and Glenoid Reconstruction (Developed by Dr. Chudik)

- Arthroscopic Hills-Sachs “Remplissage” Repair

- Arthroscopic Capsular Tear Repair-Reconstruction

- Arthroscopic Pancapsular Plication Surgery for Multidirectional (MDI) Shoulder Instability

- Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint Separation Repair and Reconstruction (Developed by Dr. Chudik)

- Sternoclavicular Separation Repair and Reconstruction

- Superior Labrum (SLAP) Tear Repair

About Dr. Chudik

- Curriculum Vitae (CV)

- Video

- Website: stevenchudikmd.com

- Schedule an appointment online

- Email: contactus@chudikmd.com

- Phone: 630-324-0402

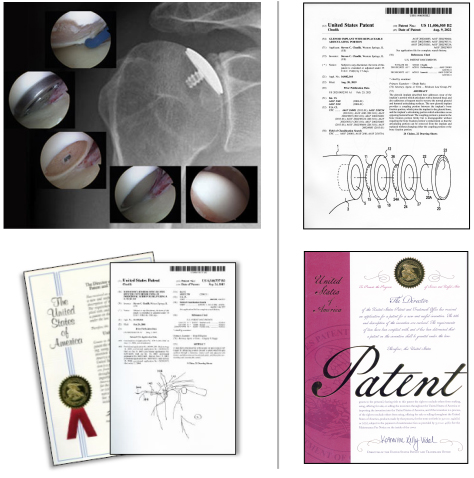

Innovations

An inquisitive nature was the impetus for Dr. Steven Chudik’s career as a fellowship-trained and board-certified orthopaedic surgeon, sports medicine physician and arthroscopic pioneer for shoulder injuries. It also led him to design and patent special arthroscopic surgical procedures and instruments and create the Orthopaedic Surgery and Sports Medicine Teaching and Research Foundation (OTRF). Through OTRF, Dr. Chudik conducts unbiased orthopaedic research and provides up-to-date medical information to help prevent sports injuries. He also shares his expertise and passion mentoring medical students in an honors research program and serve as a consultant and advisor for other orthopaedic physicians and industry research.

Novel Procedures

-

-

- Arthroscopic Repair of Humeral Avulsion of Glenohumeral Ligaments (HAGL)

- Arthroscopic Bony Bankart Repair and Glenoid Reconstruction (Developed by Dr. Chudik)

-

US Patents and Patent Applications

- Method of Minimally Invasive Shoulder Replacement Surgery, U.S. Patent No. 9,445,910, filed September 11, 2006

- Humeral Implant for Minimally Invasive Shoulder Replacement Surgery. Patent application serial number 11/529,185 case II, filed September 25, 2006

- Glenoid Implant for Minimally Invasive Shoulder Replacement Surgery, U.S. Patent No. 9,974,658, filed September 25, 2006

- Humeral Implant for Minimally Invasive Shoulder Replacement Surgery, Serial No.11/525,629, filed September 25, 2006, application published as U.S. Patent App. Pub. 2007/0016305 (A)

- Guide for Shoulder Surgery, U.S. Patent No. 9,968,459, filed September 29, 2006

- Suture Pin Device. Patent application serial number 11/529,2006, case XV, filed September 29, 2006

- Suture Pin Device, Serial No. 11/529,185, filed September 29, 2006, application published as U.S. Patent App. Pub. 2007/0027477 (A)

- Method of Arthroscopic or Open Rotator Cuff Repair Using An Insertional Guide For Delivering a Suture Pin, U.S. Patent No. 8,540,737, filed October 24, 2006

- Acromioclavicular Joint Repair System, U.S. Patent No. 9,387,011, filed February 2, 2007

- Resurfacing Implant for a Humeral Head, Serial No. 13/068,309, filed May 9, 2011, application published as U.S. Patent App. Pub. 2012/0041563 (A)

- Universal Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair and Reconstruction System(Cannulated Scalpel), U.S. Patent No. 10,034,674, filed February 2, 2007

- Resurfacing Implant for a Humeral Head. Patent application serial number 13/068,309 case II (A), filed May 9, 2011

- Method of Arthroscopic or Open Rotator Cuff Repair Using an Insertional Guide for Delivering a Suture Pin. U.S. Patent Number 8,540,737 B2, issued September 24, 2013

- Cortical Loop Fixation System for Ligament and Tendon Reconstruction, Serial No. 13/998,567, filed November 12, 2013, application published as U.S. Patent App. Pub. 2015/0134060 (A)

- Acromioclavicular Joint Repair System. U.S. Patent Number 9,387,011 B2, issued July 12, 2016

- Method of Minimally Invasive Shoulder Replacement Surgery. U.S. Patent Number 9,445,910 B2, issued September 20, 2016

- Guide for Shoulder Surgery. U.S. Patent Number 9,968,459 B2, issued May 15, 2018

- Glenoid Implant for Minimally Invasive Shoulder Replacement Surgery. U.S. Patent Number 9,974,658 B2, issued May 22, 2018

- Glenoid Implant with Replaceable Articulating Portion, U.S. Patent No. 11,406,505, filed August 20, 2019, issued August 9, 2022

- Cortical Loop Fixation Method for Ligament and Bone Reconstruction, Serial No. 15/731,719, filed July 24, 2017, application published as U.S. Patent App. Pub. 2019/0021845 (Pending)

- Humeral Implant and Method, Serial No. 17/532,714, filed November 22, 2021 (Pending), published as U.S. Patent App. Pub. US 2023/0157832

- Humeral Implant with Cannulation and Method, Serial No. 18/211,396, filed June 19, 2023 (Pending)

- Glenoid implant with Portal and Method, filed July 2023 (Pending)

Dr. Steven Chudik continually innovates to create new technology, and surgical techniques and improve patient care. He also collaborates worldwide with other leaders in the orthopaedic technology industry. Surgeries provide Dr. Chudik with an endless source of ideas to create new, safer, less invasive, and more effective surgical procedures, surgical instruments, and implants. Several of his shoulder patents are the direct result of these pioneering endeavors.

Research

An inquisitive nature was the impetus for Dr. Steven Chudik’s career as a fellowship-trained and board-certified orthopaedic surgeon, sports medicine physician and arthroscopic pioneer for shoulder injuries. It also led him to design and patent special arthroscopic surgical procedures and instruments and create the Orthopaedic Surgery and Sports Medicine Teaching and Research Foundation (OTRF). Through OTRF, Dr. Chudik conducts unbiased orthopaedic research and provides up-to-date medical information to help prevent sports injuries. He also shares his expertise and passion mentoring medical students in an honors research program and serve as a consultant and advisor for other orthopaedic physicians and industry.